Why Government Software Projects Fail — And How to Prevent It Before Writing Code

Introduction: Failure Is Not a Technology Problem

Across the world, local government software projects often fail — not because the technology is too advanced, but because the system was never designed to survive reality.

Budgets are spent, systems are delivered, and yet:

- Officers return to Excel

- Citizens still queue at counters

- Data is duplicated across departments

- Integration never truly happens

The uncomfortable truth is this:

Most government software projects fail before a single line of code is written.

The 5 Most Common Reasons Government Software Projects Fail

1. The Project Starts With Technology, Not With Problems

Many projects begin with:

- “We want a smart system”

- “We need a mobile app”

- “We should use AI / cloud / blockchain”

But they do not start with:

- What decisions need to be improved?

- What work is duplicated today?

- What information arrives too late?

Technology chosen without a clearly defined problem will always disappoint.

2. Requirements Are Written for Procurement, Not for Reality

Government requirements documents are often:

- Overly detailed in features

- Vague about actual workflows

- Written to satisfy procurement rules, not users

As a result:

- Vendors build exactly what is written

- Officers struggle with what is delivered

- Change requests explode after launch

A system that matches the document but fails in daily work is still a failed system.

3. Existing Systems Are Ignored or Underestimated

Most local governments already have:

- Finance systems

- HR systems

- Registry databases

- GIS or reporting tools

New projects often assume these can be:

- Easily replaced

- Cleanly migrated

- Or simply ignored

In reality, integration is the hardest part, and ignoring it guarantees failure.

4. Success Is Defined as “Delivered”, Not “Used”

Many projects are declared successful when:

- The system is installed

- Training is completed

- Acceptance documents are signed

But real success should ask:

- Are officers using it after 6 months?

- Has manual work actually decreased?

- Are decisions faster or better?

If usage is low, delivery means nothing.

5. No One Owns the System After Go-Live

After launch:

- Vendors move on

- Project teams dissolve

- Knowledge disappears

Without:

- Clear ownership

- Documentation

- Long-term maintenance planning

The system slowly degrades — until it is replaced again.

How to Prevent Failure — Before Writing Code

flowchart LR

%% Neutral, high-level view of how government systems typically evolve

subgraph Current_State["Current state (common today)"]

Citizens["Citizens / Businesses"] --> Channels["Service channels

(counter / phone / web)"]

Channels --> Forms["Forms & manual entry"]

Forms --> DeptApps["Department applications

(finance / HR / registry / GIS)"]

DeptApps --> Excel["Spreadsheets & shadow processes"]

Excel --> Reports["Delayed reports & duplicated data"]

end

Current_State -->|"Integration not designed"| Pain["High effort, low adoption

& frequent rework"]

subgraph Target_State["Target state (designed for reality)"]

Citizens2["Citizens / Businesses"] --> Channels2["Consistent service channels

(counter / phone / web)"]

Channels2 --> Case["Case / workflow layer

(standardized process)"]

Case --> API["Integration layer

(APIs / messages)"]

API --> Core["Existing core systems

(finance / HR / registry / GIS)"]

API --> Data["Shared data model

& governance"]

Data --> Dash["Timely dashboards & audit trail"]

end

Pain --> Principles["Preventive design principles

(decisions-first, workflow mapping,

POC validation, long-term ownership)"]

Principles --> Target_StateStep 1: Start With Decisions, Not Screens

Ask first:

- What decisions does this system support?

- Who makes those decisions?

- What information do they need, and when?

Screens and features come later.

Step 2: Map Real Workflows Across Departments

Before procurement:

- Observe how officers actually work

- Identify handoffs between departments

- Document where data is re-entered or delayed

This reveals integration needs early — when they are still cheap to solve.

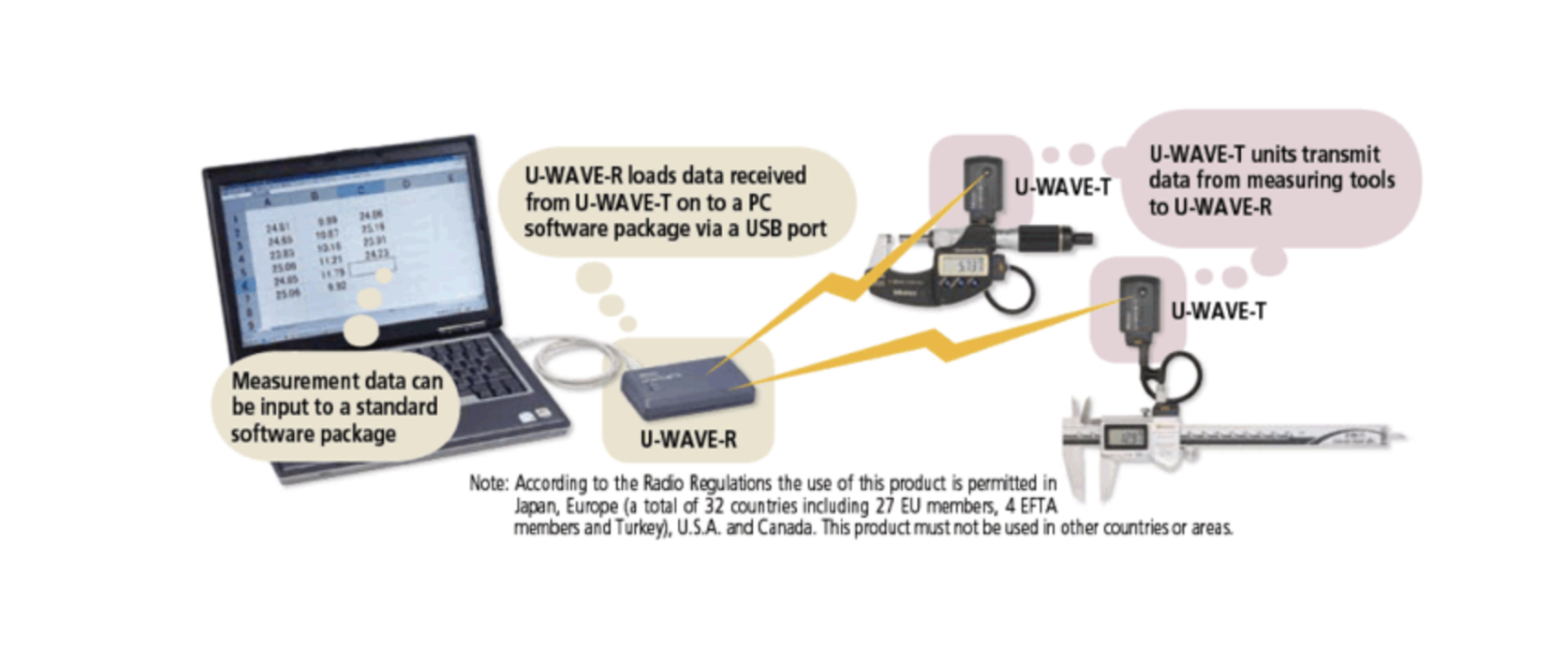

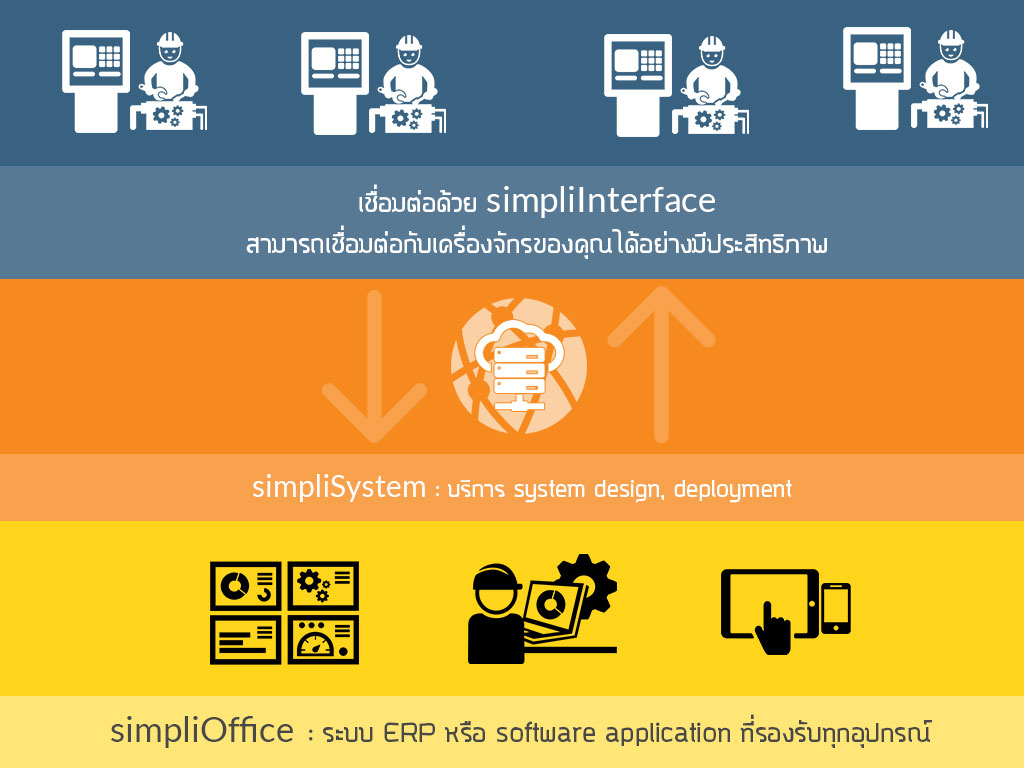

Step 3: Treat Existing Systems as Assets, Not Obstacles

Legacy systems contain:

- Institutional knowledge

- Historical data

- Critical daily operations

A good design connects them safely instead of replacing them aggressively.

Step 4: Validate With a Small Proof of Concept (POC)

Before a full rollout:

- Test assumptions with a limited scope

- Validate integration paths

- Let real users provide feedback

A small POC can prevent a large public failure.

Step 5: Design for 10 Years, Not for One Political Term

Government systems must survive:

- Policy changes

- Organizational restructuring

- Vendor changes

This requires:

- Open standards

- Clear documentation

- Transferable knowledge

The Role of Technology Consultants in Government Projects

A technology consultant’s role is not to sell software.

It is to:

- Reduce risk

- Translate policy into systems

- Protect public investment

Good consulting happens before tenders are written, not after problems appear.

Final Thought

Digital transformation in government is not about being modern.

It is about being:

- Reliable

- Sustainable

- Useful for officers and citizens

And that work must start long before coding begins.

Get in Touch with us

Related Posts

- Wazuh 解码器与规则:缺失的思维模型

- Wazuh Decoders & Rules: The Missing Mental Model

- 为制造工厂构建实时OEE追踪系统

- Building a Real-Time OEE Tracking System for Manufacturing Plants

- The $1M Enterprise Software Myth: How Open‑Source + AI Are Replacing Expensive Corporate Platforms

- 电商数据缓存实战:如何避免展示过期价格与库存

- How to Cache Ecommerce Data Without Serving Stale Prices or Stock

- AI驱动的遗留系统现代化:将机器智能集成到ERP、SCADA和本地化部署系统中

- AI-Driven Legacy Modernization: Integrating Machine Intelligence into ERP, SCADA, and On-Premise Systems

- The Price of Intelligence: What AI Really Costs

- 为什么你的 RAG 应用在生产环境中会失败(以及如何修复)

- Why Your RAG App Fails in Production (And How to Fix It)

- AI 时代的 AI-Assisted Programming:从《The Elements of Style》看如何写出更高质量的代码

- AI-Assisted Programming in the Age of AI: What *The Elements of Style* Teaches About Writing Better Code with Copilots

- AI取代人类的迷思:为什么2026年的企业仍然需要工程师与真正的软件系统

- The AI Replacement Myth: Why Enterprises Still Need Human Engineers and Real Software in 2026

- NSM vs AV vs IPS vs IDS vs EDR:你的企业安全体系还缺少什么?

- NSM vs AV vs IPS vs IDS vs EDR: What Your Security Architecture Is Probably Missing

- AI驱动的 Network Security Monitoring(NSM)

- AI-Powered Network Security Monitoring (NSM)